Skullcap Monograph

Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora) is a traditional herbal remedy with a long history of use for anxiety, insomnia, and nervous system support. In this post, explore its botany, energetics, medicinal actions, and modern research highlighting its role as a calming nervine and gentle antispasmodic. Learn how to prepare Skullcap safely and discover its place in both Western herbalism and Traditional Chinese Medicine.

HERBAL MEDICINE

Annalisa Mazzarella, BCHN®, NBC-HWC

6/11/20228 min read

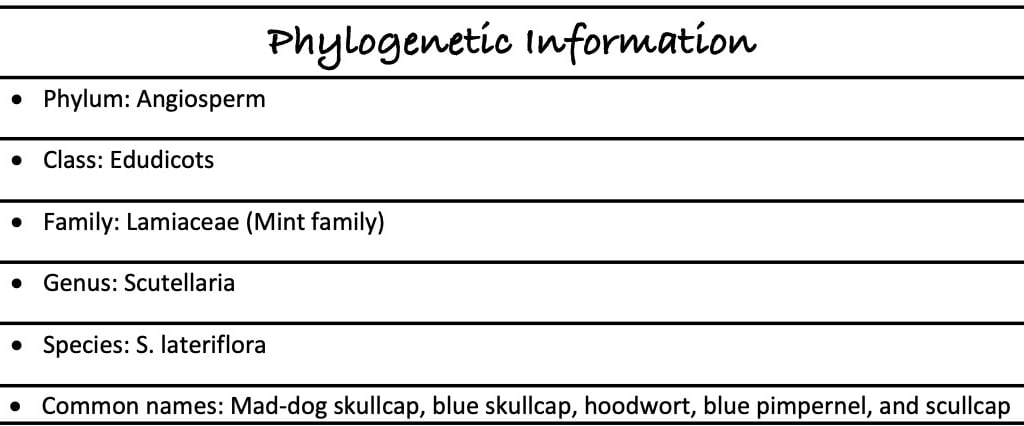

Botanical Information

Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora) is a member of the Lamiaceae (Mint) family native to eastern North America. There are more than 350 species of Scutellaria worldwide and about 100 grow in the Americas, stretching from the Artic Circle to the southern tip of South America. Most species are found in Europe and northern Asia. S. lateriflora is a perennial that grows to 1-3 feet tall and has opposite, oval or lance-shaped smooth toothed leaves with distinct venation that grow around erect square stems from which one-sided flower spikes arise. The name Scutellaria comes from the Latin word “scutella,” meaning “little dish,” probably referring to the sepals that form this dish that looks like a helmet or skullcap atop the flowers. “Lateriflora” means “flowering on the side,” likely referring to the blooms that grow along just one side of the flowering stalks. After the flowers drop, skullcap’s fruits emerge as round nutlets that are flattened on one side.

Skullcap loves woods with access to sunlight and a little acidic soil; but also open, wet meadows, and alongside streams, rivers, and lakes. Skullcap is ready for harvesting as soon as it bursts into flower. Cut the stems in the morning after the dew has dried on its leaves, and promptly use them for medicine making or dry them in hanging bunches or flat on screens in a warm, dark place with good ventilation because of their high-water content. 1,2

Look-Alikes

Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioners have used S. baicalensis (Huang-qin) for more than 2000 years, harvesting the roots for medicinal preparation in the spring after 3-4 years’ growth. It is a perennial growing to 1-2 feet tall with opposite, lance-shaped or linear leaves that have black glandular dots underneath. The flowers are blue or violet and are two-lipped, in pairs on each side of the stem. The name “baicalensis” refers to the Lake Baikal in Siberia where botanists first observed this species. It is found in dry, well-drained sandy soils in fields

or along roadsides and grows in northeastern-southern China and Russia. S. baicalensis is drought-tolerant and enjoys partial shade in warmer regions and full sun in cooler weather.

The part used medicinally is the root, which is prepared by partially drying it first, then scraping the bark off, and finally completing the drying process. With a cold energy and bitter taste, the systems affected are the heart, the lungs, liver, gallbladder, and large intestines. In TCM, the root is “primarily used as a cooling, antipyretic herb that sedates by removing the congestion of heat toxins from the heart, lungs, and liver. It is given for jaundice, suppurating infections, carbuncle, sores, pneumonia, and insecure motion of the fetus.” It is also excellent for liver yang rising (hypertension) with symptoms of irritability, red eyes, and flushed face. It is also suited to inflammatory skin conditions such as acne, eczema, and dermatitis, and has antimicrobial and antiviral properties.

3 4

Other commonly used medicinal species include S. galericulata (widespread in the Northern

Hemisphere), S. integrifolia (native to the eastern and southeastern United States), and S. californica

(native to California). However, just like with S. baicalensis, the species are not interchangeable as far as

their medicinal properties. For instance, S. californica is more bitter in taste, cooling in effect, and has

stronger digestive stimulant properties with mild liver decongestant action. So always research their

traditional uses for each specific species. Another known Skullcap look-alike is Germander (Teucrium

spp.) which has been used as a skullcap adulterant and caused hepatotoxic side effects wrongly

attributed to skullcap. Be sure to source your Skullcap from a reliable source. 5 6 7

Herbal Information

Energetics: Bitter, cooling

Constituents: the leaves contain volatile and fixed oils, flavonoids (baicalin, baicalein, scutellarin, wogonin), melatonin, serotonin, tannin, gum, sugar, a bitter principle, iridoids, and amino acid glutamine

Herbal actions: Anti-spasmodic, anti-inflammatory, anxiolytic, antioxidant, cerebral vasodilator, hypotensive, sedative, stomachic, throphorestorative for the nervous system

Plant Part Used: Flowering aerial parts

Medicinal Preparations: Tincture, infusion, and massage oil

Tincture ratios and dosage: Fresh (1:2 95%) or dry (1:5 60%); either preparation 2–5 ml (1 tsp = 5 ml), three times a day. Start with lower doses, especially during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Infusion ratios and dosage: 1–2 teaspoons (5–10 ml) of the dried leaves per 1 cup (240 ml) of boiling water, up to three times a day. For a strong infusion, use 2-9 gr per day. To make “a very strong infusion, the Eclectic guide King’s American Dispensatory recommends half an ounce of the recently dried leaves or herb to 1/2 pint of boiling water.” 8

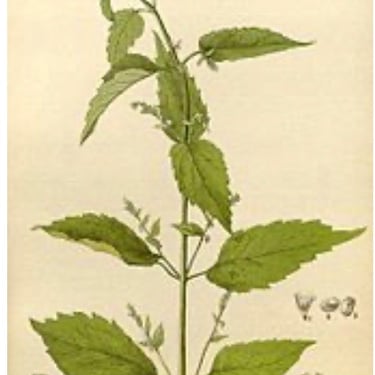

Historical Traditions and Modern Use

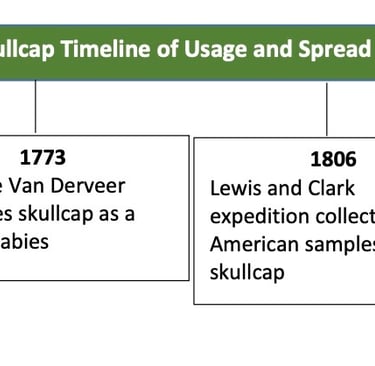

Native American tribes used to steep Skullcap leaves in a tea to promote menstruation and the roots as a remedy for diarrhea, kidney problems, and breast pain. It was also used to help deliver the placenta after childbirth and even terminate unwanted pregnancies. American settlers adopted similar practices. In American folk traditions, this herb was valued as a sedative and nerve tonic, fever reducer, and anxiety reliever. In the 1770s, it was touted as a preventative and cure for rabies, although it soon

became apparent that Skullcap could ease some symptoms, but it was not a cure. However, skullcap remained a respected remedy for treating insomnia, nervous tension, and serious mental illness like schizophrenia until the 1900s. 9 10

Relaxing Nervine

Skullcap is one of the most effective relaxing nervines and is considered a trophorestorative herb to the central nervous system. Modern herbalists use this herb to sooth anxiety, ease nervous restlessness, and relieve insomnia. Flavonoids Baicalin and Baicalein—found in Scutellaria— are known to bind to GABA, which is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain that promotes calmness and relaxes muscle tensions. Based on some pharmacological data, flavonoid interactions with the GABA-A receptor may be involved in skullcap’s mechanism of action.11 In 2003, a small randomized controlled study provided 19 healthy volunteers with a placebo, 100-, 200-, or 350-mg capsules of a freeze-dried skullcap extract and asked them to rate their anxiety an hour later. The volunteers taking the 2 higher doses showed a significant reduction in anxiety levels.12 Another randomized, double-blind study using healthy volunteers found that skullcap “significantly enhanced global mood without a reduction in energy or

cognition.”13 Herbs that bind GABA receptors can indeed help soothe anxiety, panic attacks, insomnia, stress-induced hypertension, and nervous exhaustion. Skullcap doesn’t promote daytime sleepiness for most people, and it is considered safe for children, elders, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers, although “safety has not been conclusively established.” 14

Herbalist and Licensed Acupuncturist Thomas Garran points out that Jing-Nua Wu in Chapter 8 of “Ling Shu” describes how Skullcap is effective at supporting drug (including alcohol) addiction detoxification because of its excellent ability to relieve heart depression and therefore “…affect the greatest hurdles in hell many people experience when trying to deal with a severe or long-term drug addiction.” Furthermore, Garran adds that because of its profound effect on the liver, “Skullcap can help with many of the physical manifestations of withdrawal.”

Herbalist Robin Rose Bennet also points out that Skullcap’s deep nervine powers can help soothe heartbreak, grief, shock, and trauma, as well as assist those experiencing postpartum depression and anxiety in pregnancy. Those who are prone to overanxious states brought by sensory stimuli like crowds, loud music, and storms will find a great ally in Skullcap, too. 15 16 17

Gentle antispasmodic

Skullcap is also an excellent antispasmodic, anodyne, and skeletal muscle relaxant that can ease tension associated with nervous and muscular headaches, fibromyalgia, nerve inflammation, and anorexia nervosa. It is especially indicated for those who experience anxiety-related tremors, spasms, and tics. It can be used to great benefit for sciatica, trigeminal neuralgia, shingles, and menstrual cramps. Herbalist David Winston recommends Skullcap for an even wider range of conditions including restless leg

syndrome, bruxism (teeth grinding), mild Tourette’s syndrome, tardive dyskinesia (involuntary movements of the muscles and tongue), petit mal seizures, neck and back pain, and panic disorders. For spasms and spasmodic pain, Skullcap is better as a preventive than as an acute remedy; it should be given tonically between episodes. An infused massage oil is also a nice option. In TCM, Skullcap is also used to stimulate digestion, promote urination, and as an antidote for snake poison. 18 19

Recipes

The Chestnut School of Herbal Medicine suggests combining Skullcap with:

Tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) and Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) for general anxiety (acutely or tonically); with Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) for panic attacks; and with Milky oats (Avena sativa) for nerves that are constantly on edge.

Hops (Humulus lupulus) and Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) for a strong “sleepy” infusion, which s generally more sedating than the tincture…“drink a cup of the tea about an hour before bedtime—this way you (hopefully) won’t awaken to pee.”

Garran suggests combining Skullcap with Chinese Red Sage (Salvinia miltiorrizha) and Ziziphus (Z. spinosa) for depressive heart patterns with anxiety, nervousness, palpitations, and preoccupation. To support drugs withdrawal symptoms, he recommends adding California poppy (Eschscholzia californica),

Passion Flower (Passiflora incarnata), “and a bit of Licorice” (Glycyrrhiza glabra). For depressive patterns of the liver with symptoms of dysmenorrhea, flank pain, and chest pain, he proposes a combination of Skullcap, Bupleurum (B. chinense), and White Peony (Paeonia lactiflora); in case of heart and liver depressive patterns with depression, anxiety, sighing, and oppression in the chest, he proposes to combine Skullcap to Kava (Piper methysticum), Albizia (A. julibrissin), Cyperus (C. rotundus), and Rose

buds (Rosa spp.). 20 21 You can mix equal parts of herbs and follow dosage recommendations covered above.

Precautions and Contraindications

Skullcap can cause jittery nerves and giddiness in some people, especially when taken in large doses. Always start with a low dose when exploring your tolerance. Reports of liver toxicity were likely related to historical adulteration with germander (Teucrium spp.). Although skullcap is generally considered safe in pregnancy with no adverse events reported, there haven’t been any conclusive studies done on its safety. 22

references:

1 Johnson, Foster, Low Dog, Kiefer, “National Geographic Guide to Medicinal Herbs,” 2010

2 Chestnut School of Herbs, “Skullcap Monograph,” https://chestnutherbs.com/lesson/skullcap-scutellaria-

lateriflora/

3 Michael Tierra, “The Way of Herbs,”1998

4 Micahel Tierra, “The Way of Chinese Herbs,” 1998

5 David Hoffman, “Medical Herbalism – the Science and Practice of Medical Herbalism,” 2003

6 Chestnut School of Herbs, “Skullcap Monograph,

” https://chestnutherbs.com/lesson/skullcap-scutellaria-

lateriflora/

7 Peter Holmes, “The Energetics of Western Herbs: A Materia Medica Integrating Western & Chinese Herbl

Therapeutics,” Vol. II, 2006

8 Herbmentor, “Skullcap Monograph,” https://herbmentor.learningherbs.com/herb/skullcap/#marker-37491-3

9 Dr. Sharol Tilgner, “Herbal ABCs, The Foundation of Herbal Medicine,” 2018

10 Moerman, D. E. “Native American Ethnobotany,” 1998

11 Upton R, ed. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and Therapeutic Compendium: Skullcap Aerial Parts. Scotts Valley,

CA: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia; 2009.

12 Wolfson P, Hoffmann DL, “An investigation into the efficacy of Scutellaria lateriflora in Healthy Volunteers,”

Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 2003

13 Christine Brock et al., “American Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora): A Randomised, Double-Blind Placebo-

Controlled Crossover Study of Its Effects on Mood in Healthy Volunteers,” Phytotherapy Research: PTR 28, no. 5

(May 2014): 692–98, https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5044

14 AHPA “Botanical Safety Handbook,” 2nd Edition, 2013

15 Dr. Jill Stansbury, “Herbal formularies for Health Professionals,” Volume 4, 2020

16 Thomas Avery Garran, “Western Herbs according to Traditional Chinese Medicine,” 2008

17 Bennett, R. R.,

“This Gift of Healing Herbs: Plant Medicines and Home Remedies for a Vibrantly Healthy Life,”

2014

18 Chestnut School of Herbs, “Skullcap Monograph,” https://chestnutherbs.com/lesson/skullcap-scutellaria-

lateriflora/

19 Peter Holmes, “The Energetics of Western Herbs: A Materia Medica Integrating Western & Chinese Herbl

Therapeutics,” Vol. II, 2006

20 Chestnut School of Herbs, “Skullcap Monograph,” https://chestnutherbs.com/lesson/skullcap-scutellaria-

lateriflora/

21 Thomas Avery Garran, “Western Herbs according to Traditional Chinese Medicine,” 2008

22 AHPA “Botanical Safety Handbook,” 2nd Edition, 2013

"If you truly love nature, you will find beauty everywhere"— Vincent Van Gogh

Contact us:

info@wildwoodsherbals.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.

My post content