Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): An Integrative, Whole‑Person Approach

PCOS is complex—but understanding it changes everything. From hormonal imbalances and insulin resistance to nutrition, botanicals, stress, and sleep, this article explores PCOS through an integrative, whole-person lens. If you want to better understand your body and feel empowered in your care, keep reading!.

HEALTH & WELLNESS

Annalisa Mazzarella, BCHN®, NBC‑HWC

12/17/20259 min read

What is PCOS?

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common—and most misunderstood—endocrine disorders affecting women of reproductive age. Often framed narrowly as a fertility issue, PCOS is now recognized as a lifelong metabolic and hormonal condition with reproductive, cardiometabolic, dermatologic, and psychological dimensions.

This article is adapted from my doctoral presentation and clinical talking points, designed to help potential clients better understand what PCOS is, why it develops, and how an integrative, evidence-informed approach can support long-term health and quality of life.

PCOS is a complex endocrine‑metabolic disorder characterized by a combination of:

Irregular or absent ovulation

Hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical signs of excess androgens)

Polycystic ovarian morphology on ultrasound

Several professional organizations define PCOS slightly differently:

NIH (1990): Hyperandrogenism + chronic anovulation

Rotterdam Criteria (2003): Any two of the three features above

AE‑PCOS Society (2009): Hyperandrogenism + ovarian dysfunction

Importantly, PCOS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Thyroid disorders, hyperprolactinemia, and adrenal causes of hyperandrogenism must always be ruled out.

PCOS affects an estimated 5–26% of women worldwide, depending on the diagnostic criteria used. It occurs in both lean and higher‑BMI individuals and is frequently underdiagnosed. In the United States alone, the annual cost of diagnosing and treating PCOS is estimated at $3.7 billion, reflecting not only reproductive care but also long‑term metabolic and cardiovascular complications.

Prevalence and Public Health Impact

PCOS Phenotypes: Why One Size Does Not Fit All

PCOS is not a single presentation. Four phenotypes (A–D) are recognized based on which diagnostic features are present. Phenotype A—the most severe—includes hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and polycystic ovaries.

Understanding phenotype matters because:

Risk profiles differ (e.g., metabolic vs reproductive dominance)

Symptoms can shift over time

Health strategies should be individualized

Symptoms and Clinical Features

PCOS extends far beyond menstrual irregularities. Common features include:

Irregular or absent periods

Infertility

Acne, hirsutism, and scalp hair thinning

Weight gain and insulin resistance

Anxiety, depression, and reduced quality of life

As PCOS is now widely recognized as a chronic metabolic condition, not simply a gynecologic disorder with long-term risks, women with PCOS face increased risk of:

Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome

Gestational diabetes and pregnancy complications

Cardiovascular disease

Metabolically associated fatty liver disease (MASLD)

Endometrial hyperplasia and cancer

Sleep apnea and mental health challenges

A central driver of these risks is the self‑perpetuating cycle of insulin resistance, androgen excess, and visceral adiposity.

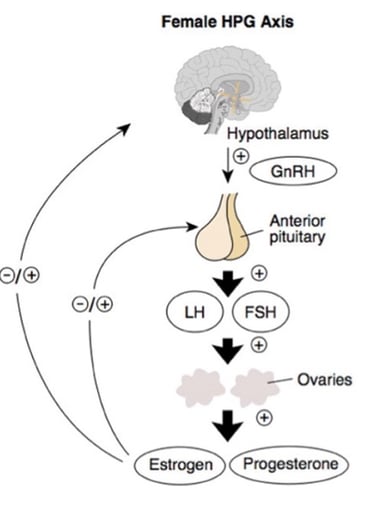

Hormonal Physiology: What Goes Wrong in PCOS?

In a healthy hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis, the hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in a balanced, rhythmic pattern that stimulates the pituitary to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in appropriate proportions. FSH supports ovarian follicle maturation, while a mid-cycle surge of LH triggers ovulation. Estrogen and progesterone then provide negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary, helping regulate hormone production and maintain regular menstrual cycles.

In polycystic ovary syndrome, this finely tuned system becomes dysregulated. Rapid GnRH pulsatility favors disproportionately high LH and relatively low FSH levels, which stimulate excess ovarian androgen production while impairing proper follicle development. As a result, follicles fail to mature, and ovulation does not occur. At the same time, insulin resistance reduces levels of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), increasing the amount of free, biologically active androgens in circulation. These androgens are further converted to estrone in adipose tissue, creating abnormal feedback signals that perpetuate LH dominance. Together, these mechanisms drive the hallmark features of PCOS: persistent hyperandrogenism, chronic anovulation, and ongoing metabolic stress.

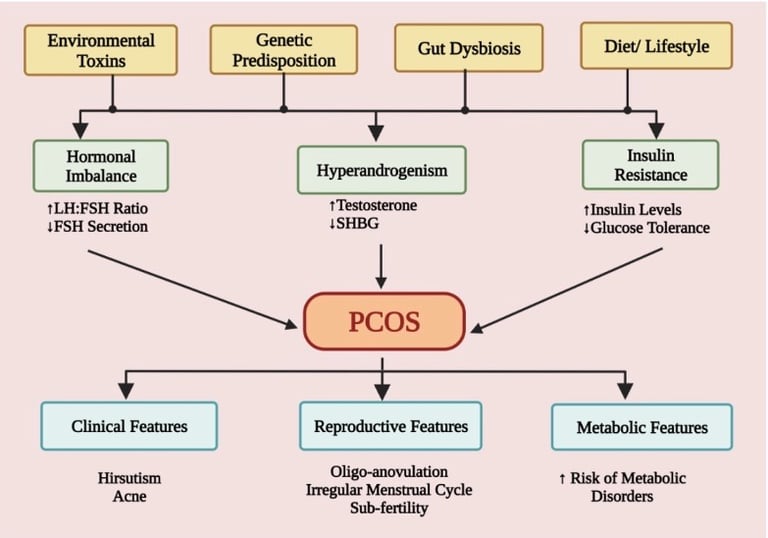

Pathophysiologic Triggers

PCOS does not have a single cause. Instead, it arises from a convergence of genetic susceptibility and environmental influences that interact across the lifespan. Research suggests that genetic variants affecting insulin signaling, steroid hormone production, and inflammatory pathways can predispose some individuals to PCOS. These genetic tendencies may be amplified by epigenetic changes, particularly those occurring in utero or early life, which can alter how genes are expressed without changing the DNA itself. Prenatal exposure to excess androgens or environmental toxins may prime the body for hormonal dysregulation years before symptoms appear.

Diet and lifestyle factors play a central role in whether this predisposition becomes clinically expressed. Diets high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and ultra-processed foods promote insulin resistance and chronic inflammation—two key drivers of PCOS. Central (abdominal) adiposity further worsens insulin signaling and increases ovarian and adrenal androgen production. Importantly, even modest, sustainable lifestyle changes—such as a 5–10% reduction in body weight for those who are overweight or obese—have been shown to improve menstrual regularity, ovulation, and metabolic markers.

Emerging research also highlights the role of the gut microbiome in PCOS. Women with PCOS often exhibit reduced levels of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, alongside increased gut permeability. This imbalance may allow inflammatory compounds like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to enter circulation, contributing to systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and androgen excess. Environmental exposures further compound this burden. Air pollution, cigarette smoke, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals—including BPA, PFAS, and phthalates—have all been associated with hormonal disruption and increased PCOS risk, with some evidence suggesting transgenerational effects.

Conventional management of PCOS typically focuses on regulating menstrual cycles, reducing androgen-related symptoms, supporting fertility, and mitigating long-term metabolic risks. Diagnosis often includes blood work to assess LH, FSH, androgens, as well as metabolic markers, along with ultrasound imaging when indicated. Equally important is ruling out other endocrine conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, or adrenal disorders.

Pharmacologic treatment options may include oral contraceptives to regulate cycles, metformin or inositols to improve insulin sensitivity, anti-androgens for acne or hirsutism, and ovulation-inducing medications for fertility support. While these interventions can be helpful, they often manage symptoms rather than address upstream drivers. Lifestyle modification—nutrition, movement, and weight management when appropriate—remains the cornerstone of care and consistently shows the most substantial long-term benefits.

It is also essential to consider drug–nutrient interactions. For example, long-term metformin use may deplete vitamin B12, while oral contraceptives can lower folate, B6, magnesium, and zinc. Without nutritional monitoring, these imbalances may quietly worsen fatigue, mood symptoms, or metabolic health over time.

Integrative Care: Addressing Root Causes

An integrative approach to PCOS expands the focus beyond symptom suppression to restoring metabolic and hormonal balance at the root. Evidence increasingly supports multimodal interventions that combine nutrition, targeted supplementation, botanical medicine, physical activity, stress regulation, and sleep support. Together, these strategies reduce insulin resistance, inflammation, and oxidative stress while improving hormonal signaling.

Diet is one of the most powerful tools available. Dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean, DASH, and low-glycemic diets have consistently demonstrated improvements in insulin sensitivity, androgen levels, and menstrual regularity. These approaches emphasize whole foods, fiber-rich vegetables, high-quality proteins, healthy fats, and minimal refined carbohydrates—supporting both metabolic health and hormonal regulation.

Targeted nutraceuticals may also play a supportive role when used individually, under the guidance of a professional. Myo- and D-chiro-inositol support ovarian function and insulin signaling, while omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants help reduce chronic inflammation. Vitamin D has been associated with improved ovulation and reduced androgen synthesis, and minerals such as chromium may enhance insulin receptor sensitivity. Quality, dosing, and safety monitoring are critical, particularly for long-term use.

Botanical medicine offers additional support when used appropriately. For example, berberine-containing herbs activate AMPK pathways similar to metformin, cinnamon improves insulin sensitivity, turmeric reduces inflammatory signaling, and Vitex supports dopaminergic regulation of prolactin. Licorice root (not deglycyrrhinized) has been shown to have androgen-lowering effects, while other herbs, such as fennel, white peony, sage, black cohosh, and vitex (among others) have been traditionally used to support hormonal and cycle balance. Botanical interventions should always be personalized, quality-controlled, monitored, and assessed for potential herb–drug interactions.

Lifestyle Foundations: Movement, Stress, and Sleep

Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammation, and supports ovulatory function. Research supports a combination of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and resistance training, with a goal of at least 150 minutes per week. Even small increases in daily physical activity can yield significant metabolic benefits, particularly for individuals transitioning from a sedentary lifestyle.

Stress management is equally critical. Chronic stress exacerbates HPA-axis dysregulation and insulin resistance, thereby amplifying hormonal imbalances. Mind-body practices, including yoga, meditation, journaling, acupuncture, and mindfulness-based stress reduction, have been shown to benefit metabolic markers, mood, and perceived health. Cognitive-behavioral strategies and coaching support can further help address body image concerns, anxiety, and long-term adherence.

Sleep is often overlooked, yet it has a profound influence on hormonal regulation. Poor sleep disrupts the signaling of leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol, leading to increased appetite and insulin resistance. Supporting sleep hygiene—consistent schedules, reduced screen time, and calming evening routines—can significantly enhance overall treatment outcomes.

Conventional Care: What It Addresses—and What It Misses

Bringing It All Together

Effective PCOS care is not about a single intervention—it is about integration. Combining nutrition, movement, stress regulation, and sleep support within a realistic and personalized framework yields the most sustainable results. Health coaching and motivational interviewing help translate knowledge into action by supporting SMART goals, accountability, and long-term behavior change.

Ultimately, success in PCOS care should be measured not only by menstrual regularity or fertility outcomes, but by improved metabolic health, emotional well-being, and quality of life. An integrative, whole-person approach empowers individuals to become active participants in their healing—addressing PCOS not in silos, but as a dynamic, interconnected condition that responds to informed, compassionate care.

REFERENCES

Abdolahian, S., Tehrani, F. R., Amiri, M., Ghodsi, D., Yarandi, R. B., Jafari, M., Majd, H. A., & Nahidi, F. (2020). Effect of lifestyle modifications on anthropometric, clinical, and biochemical parameters in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 20(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00552-1

Abdulla, M. L., Shathir, A. N., Anwaru, S., Ahmed, A. S., Ismail, F. I., Shabin, A., & Ali, S. (2024). Emerging infertility biothreat and gynecological pandemic polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): Molecular biogenesis with emphasis on treatment. Pharmacophore, 15(2), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.51847/smn018b4hw

Azziz, R., Carmina, E., Dewailly, D., Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., Escobar-Morreale, H. F., Futterweit, W., Janssen, O. E., Legro, R. S., Norman, R. J., Taylor, A. E., Witchel, S. F., & Task Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. (2009). The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: The complete task force report. Fertility and Sterility, 91(2), 456–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035

Dema, H., Videtič Paska, A., Kouter, K., Katrašnik, M., Jensterle, M., Janež, A., Oblak, A., Škodlar, B., & Bon, J. (2023). Effects of mindfulness-based therapy on clinical symptoms and DNA methylation in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and high metabolic risk. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 45(4), 2717–2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb45040178

Di Lorenzo, M., Cacciapuoti, N., Lonardo, M. S., Nasti, G., Gautiero, C., Belfiore, A., Guida, B., & Chiurazzi, M. (2023). Pathophysiology and nutritional approaches in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A comprehensive review. Current Nutrition Reports, 12(3), 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-023-00479-8

Gautam, R., Maan, P., Jyoti, A., Kumar, A., Malhotra, N., & Arora, T. (2025). The role of lifestyle interventions in PCOS management: A systematic review. Nutrients, 17(2), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020310

Hafizi Moori, M., Nosratabadi, S., Yazdi, N., Kasraei, R., Abbasi Senjedary, Z., & Hatami, R. (2023). The effect of exercise on inflammatory markers in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. International Journal of Clinical Practice. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3924018

Khatlani, K., Njike, V., & Costales, V. C. (2019). Effect of lifestyle intervention on cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 17(10), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2019.0049

Kim, K. W. (2021). Unravelling polycystic ovary syndrome and its comorbidities. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome, 30(3), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes21043

Menichini, D., Ughetti, C., Monari, F., Di Vinci, P. L., Neri, I., & Facchinetti, F. (2022). Nutraceuticals and polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review of the literature. Gynecological Endocrinology, 38(8), 623–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2022.2089106

Moslehi, N., Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S., Rahimi Sakak, F., Shab-Bidar, S., Tehrani, F. R., & Mirmiran, P. (2023). Effects of nutrition on metabolic and endocrine outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Reviews, 81(5), 555–577. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac075

Muhammed Saeed, A. A., Noreen, S., Awlqadr, F. H., Farooq, M. I., Qadeer, M., Rai, N., Farag, H. A., & Saeed, M. N. (2025). Nutritional and herbal interventions for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A comprehensive review of dietary approaches, macronutrient impact, and herbal medicine in management. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 44(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-025-00899-y

Riestenberg, C., Jagasia, A., Markovic, D., Buyalos, R. P., & Azziz, R. (2022). Health care–related economic burden of polycystic ovary syndrome in the United States: Pregnancy-related and long-term health consequences. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 107(2), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab613

Sarris, J., & Wardle, J. (2019). Clinical naturopathy: An evidence-based guide to practice (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

Singh, S., Pal, N., Shubham, S., Sarma, D. K., Verma, V., Marotta, F., & Kumar, M. (2023). Polycystic ovary syndrome: Etiology, current management, and future therapeutics. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041454

Stansbury, J. (2019). Herbal formularies for health professionals: Volume 3, Endocrinology. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Teede, H. J., Tay, C. T., Laven, J. J. E., Dokras, A., Moran, L. J., Piltonen, T. T., Costello, M. F., Boivin, J., Redman, L. M., Boyle, J. A., Norman, R. J., Mousa, A., Joham, A. E., & International PCOS Network. (2023). Recommendations from the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Endocrinology, 189(2), G43–G64. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejendo/lvad096

"If you truly love nature, you will find beauty everywhere"— Vincent Van Gogh

Contact us:

info@wildwoodsherbals.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.

My post content